The Capital Preservation Allowance

In earlier blogs, I explained my views about depreciation; both its irrelevance in business decision-making and the way it is treated as a fixed annual cost. An organization does, however, need to provide for the preservation of its existing capital based as it sells products and services to customers. One way to accomplish that is to develop a Capital Preservation Allowance. I first proposed this solution in an article titled “A Modest Proposal for Pricing Decisions” that appeared in the March 1993 issue of Management Accounting. This allowance is a long-term, forward-looking view of capital requirements that replaces depreciation in the calculation of product and process cost and enables a company to effectively accumulate the funding required from current products and services to preserve existing productive capabilities.

A company whose capital assets form a single system that is used to produce nearly all of its products or generate its services can develop a single Capital Preservation Allowance (or CPA – not to be confused with accountants bearing that moniker) for all of its future capital requirements. A company with several lines of business, each with different levels of future capital needs, may need several CPAs – one for each line of business. In job shops, where different asset types have different future capital needs, a different CPA may be needed for each unique type of asset. Regardless of the situation, however, the CPA must look to the future, not the past.

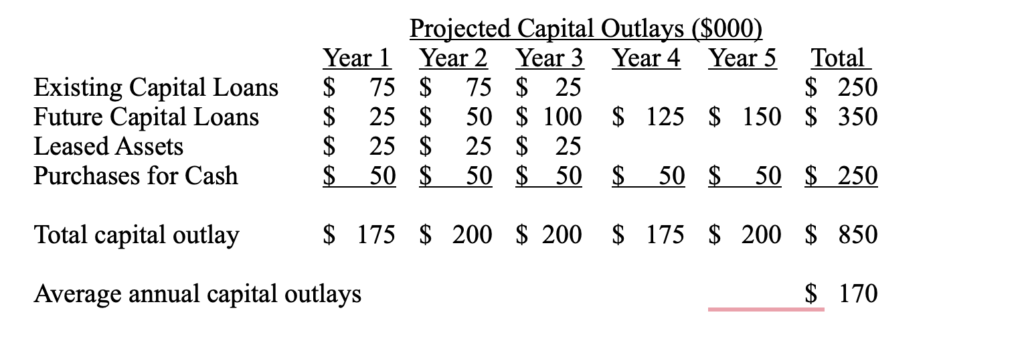

The mechanics of a Capital Preservation Allowance are not complex. In principle, it is like establishing a “sinking fund” to provide for future capital outlays. The simplest approach is to forecast necessary capital outlays for a representative number of years. For CPA purposes, capital outlays mean principal payments on existing and future loans used to finance capital purchases, payments made for currently leased assets, and any capital assets purchased for cash – the annual cash requirements to fund preservation of the asset base. For example, one company anticipates the following expenditures to preserve its existing production capabilities over the next five years:

The simplest way to incorporate this $170,000 average annual amount into the company’s cost structure is to establish a $170,000 Capital Preservation Allowance and add it to product cost as a percentage of activity costs. The shortcoming of this approach is that, like depreciation expense, it assumes that the need to replace assets is based on chronological time, not usage. This, in turn, allows for a wide fluctuation in rates from year-to-year due to fluctuations in the company’s volume of business. Preserving the capital base is a long-term proposition and as such should not be impacted by short-term events. Instead, it should reflect the long-term sustainable economics of the business.

A better way would be to tie at least a portion of the CPA to the usage of the assets. For example, if the existing group of assets, including those that will replace them, are expected to operate for 85,000 hours during the five-year period, a CPA of $10.00 per machine hour could be established. This would eliminate variations in each year’s CPA amount just because of volume swings. Without this long-term view, a year in which machine hours are 15,000 would generate a CPA of $11.33 and a year in which they are 20,000 would generate a CPA of $8.50. Such annual variations do not reflect the true long-term nature of funding capital expenditures.

Since some capital assets become obsolete over time while others wear out through usage, the ideal solution might be to create a time-based Capital Preservation Allowance for those assets that must be replaced due to the passage of time and a usage-based CPA for those that physically wear out. Either way, a Capital Preservation Allowance will provide a more accurate measure of the capital funds that must be generated through the sale of the company’s products and services just to maintain the status quo. The CPA is intended to cover the preservation of existing capabilities, not the expansion of those capabilities. Capital expenditures made to support growth are funded by the profits generated by the sale of current products and services; they are not a cost attributable to them

Conclusion

The inclusion of depreciation expense in any cost information developed to support management’s decisions or actions is a serious mistake. Depreciation is simply the manipulation of sunk costs and we all know that sunk costs are irrelevant. To simply preserve its existing volume of business, a company must be able to accumulate the funds required to preserve its capital asset base through the sale of the products and services. As a result, it needs to create a forward-looking mechanism that will insure an adequate flow of funds is being provided to preserve that asset base. The Capital Preservation Allowance is one such mechanism.

There are many refinements that can be made to more accurately include a CPA in the cost of products and services. The critical issue is to make sure a company looks to the future, not the past, in determining the capital expenditure costs to include in your company’s products and processes.

Read Doug’s next article, Depreciation – Fixating on the Irrelevant.

Written by Doug Hicks

Author, speaker, educator and President of D. T. Hicks & Co., a consulting organization concentrating on the managerial costing needs of small and mid-sized organizations. A graduate of the University of Michigan – Dearborn’s School of Management and a member of the Michigan Association of CPAs, the Institute of Management Accountants, and the Executive Board of the Society of Cost Management.